Developing Wisdom Part 3: Action

The final main installment in a series on how to develop wisdom.

In Part 1 and Part 2 of this series, I explained my basic argument that general wisdom is developed by, first, adopting an attitude of humility that opens a person to learning from the experiences of life, and, second, from actually weathering those experiences over a long time. It is through these experiences that a person can gain not simply knowledge, but adeptness with the use of knowledge beyond what intelligence and reason can provide alone. With this kind of wisdom, a man is more capable of making correct decisions, particularly when an important factor is dealing with a significant lack of knowledge.

In this part, we turn to the final of the three major components of wisdom as I currently see it: action. In short, an intellectual decision alone is not the end purpose of wisdom. The end purpose is to make good decisions in one’s life, and this entails actually doing whatever was determined to be the wise course of action. Having reached a wise decision intellectually is commendable, but if it is not actually acted on then it fails its ultimate purpose, to have a good effect on one’s life. It would be the practical equivalent of having decided to do nothing.

It might be thought that this is so obvious it is unnecessary to include in a discussion on wisdom, but I disagree for a few reasons. First, we know this needs to be discussed because it is the point of so much failure for many people. Incomplete projects, unfulfilled promises, goals never started on, and pursuits abandoned are common regrets for people today. It is therefore not always for lack of intellectual wisdom that we don’t experience wisdom in our lives, leaving the problem of action as the frequently missing piece. Second, even when a wise course of action is decided, carrying out that course of action effectively requires a practical wisdom of its own. It may be wise to start a business, but do you know how to run a business well? It may be wise to get married, but do you know how to lead a wife faithfully? And, third, there is a component of action that requires a kind of motivation, something from within that is more than an intellectual decision to act, but an ability to overcome fear, uncertainty, and apathy that could otherwise paralyze action.

Foolishness or inaction?

When we find ourselves taking a wise course of action, we often like to think of ourselves as being more intelligent than all those who acted foolishly instead. We feel as if we are “better” than everyone else who seem content to roll around in the muck of their bad decisions. A common reality, I think, is that often when people make foolish choices, it isn’t because they weren’t smart enough to make the wiser choice, but because the wiser choice involved something displeasurable or difficult that they didn’t want to do. We pat ourselves on the back for outsmarting the crowds of fools who waste their money on gambling, when perhaps they know as well as we do how foolish it is but are simply unwilling to forego the temporary enjoyment it brings them or endure the discomfort of giving it up. We might consider a smoker foolishly compromising his health, but we can all understand that it may be addiction rather than ignorance that makes him do it.

So, simply understanding good and bad cannot be the end of wisdom, or we would have to count all of these people wise as well.

Knowing how to transfer wise decisions into corresponding wise action is the final link in reaching true wisdom. Of course, this implies that true wisdom is not merely an intellectual question, but one of actually ordering a person’s life in a better way. And, since it is my definition of wisdom we are talking about here, this is exactly what true wisdom means for our purposes.

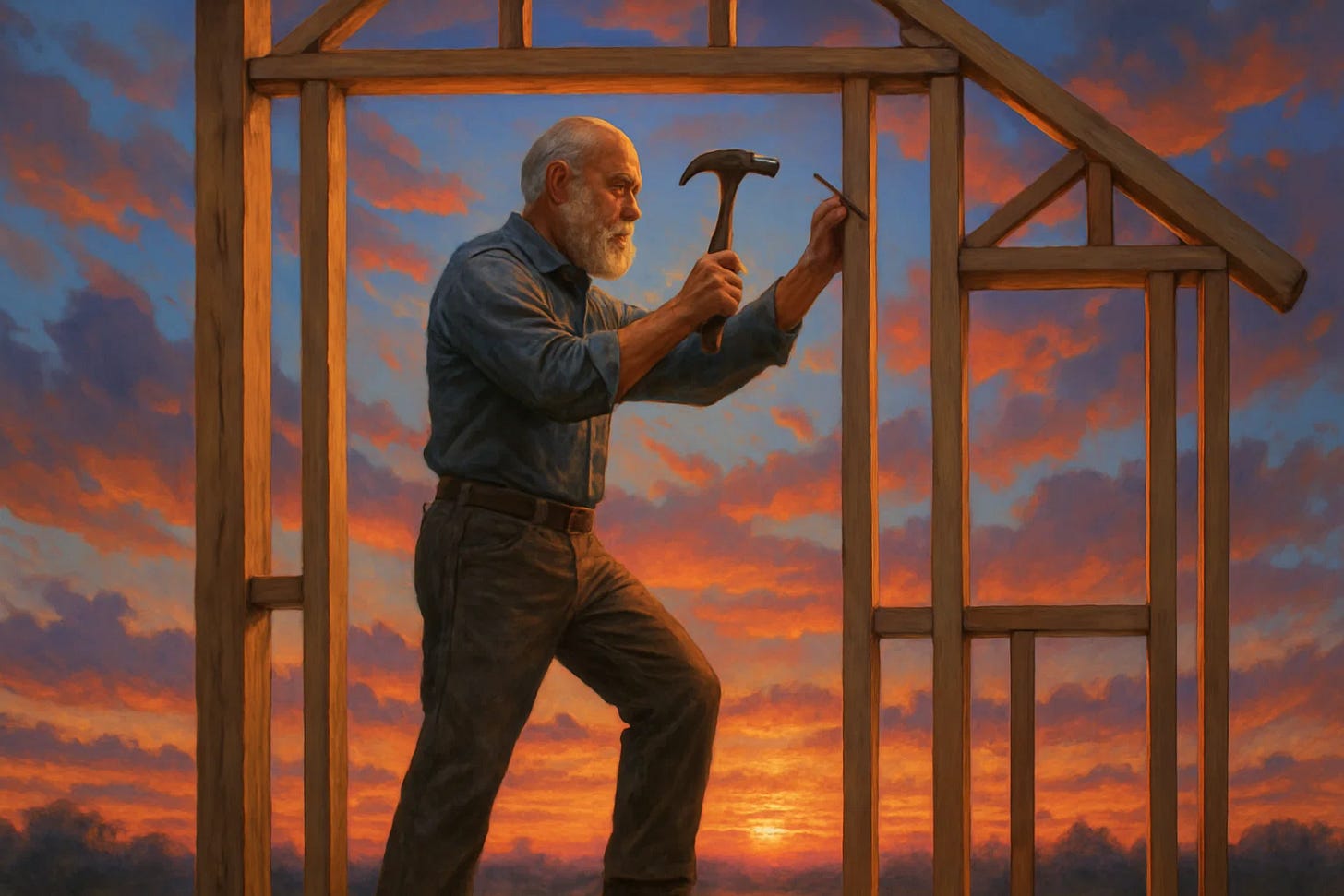

Yet, while the first two parts of this series, outlining humility and experience, were very nearly a unified subject, this part on action is a bit different. Action is a concrete step out into the physical world, beyond the merely intellectual one. One must first exercise intellectual wisdom before he has opportunity to put it into the real world through action. In action, the focus of the wisdom that is used moves from the mind to the hands.

Of course, the hands are controlled by the mind, so the wisdom in action is still technically a product of the mind. It is thus still foolishness to fail to do something through inaction. The difference with action is that it contemplates what the mind does after a decision is made. I now regret using the term “practical wisdom” in the past to refer to what I am now referring to as the “intellectual” side of wisdom, because “practical wisdom” would be a useful label to qualitatively differentiate the kind of wisdom-in-practice involved in action. I will refer to it as “applied wisdom,” and hope I don’t later find a better use for that term as well and have to scrap my whole labeling convention altogether.

The applied wisdom of skill

Everyone has had the experience of suddenly deciding to do something grand and being excited about doing it right up to the point of actually having to figure out how to do it. Commitments that begin, “I ought to lose weight” or “I should write a book,” often end unceremoniously before any serious steps are taken. What will be involved in losing weight? Should I read this entire book on weight loss first? Will I have to learn to cook new meals?

Something I tend to notice with quite successful people is that they have found a niche in which they do one thing very well. I don’t mean the few extremely successful billionaire class types who have the uncanny ability to succeed in multiple ventures and prosper through diverse efforts. I mean the well off person on your street, or the wealthiest people in your town. There are exceptions, but among those who earned their own success, you typically find that they apply themselves in a narrow field. The fact is, a normal person can only get really good at a few things in a single lifetime.

There was a book called “Outliers” by Malcom Gladwell that gained prominence about a decade ago because the author claimed to have discovered that mastery of an endeavor was a simple formula of practicing that skill for 10,000 hours. This was the secret to all of the elite superstars like basketball players who had logged 10,000 hours of drills and playtime by the time they entered the NBA draft. It didn’t matter the subject, sports, games, professions, hitting 10,000 hours was a kind of boundary that the human body and mind somehow responded to by becoming an expert at that thing once the requisite number of hours was reached. It was a little more complicated than that, but that was the gist: 10,000 hours is how long a person requires to maximize skill in an area. Eventually, I felt like I saw through what Gladwell had done in his argument. I think 10,000 hours is simply the maximum amount of time available to a person during the first 20 or so years of his life to devote to practicing any one skill. It isn’t a magic number, it is just that if you have spent 10,000 hours on something, then you will have devoted more time to it than anyone else, because there literally is no more time anyone could have spent on it, and most people have multiple interests. You’re simply the best at the thing, and it turns out that when we say “expert,” we just mean the best. Thus, 10,000 hours is just a measurement of the most hours a person can spend on any one thing by the time it comes to compete.

The truth about skill, then, is that there are no objective levels that define an expert or a beginner. An “expert” is just someone who is better at something than almost everyone else. It isn’t defined as having 98% of all the possible skill in a subject, because there is no limit to skill and you could always be a little better if you had more time in practice. A sculptor, no matter how great he seems, could always be better. His sculptures could always be just a bit more lifelike, could have a bit more dramatic relief, could use shadows a bit more effectively, could capture the essence of a scene a bit more vividly, and so on. But to reach that next level of skill, a person would need 11,000 hours of practice, which amount of time simply doesn’t exist. Yet, a sculptor who somehow had that amount of practice would be objectively better at sculpture than anyone else. What counts as an expert would change. An expert would now just be someone with 11,000 hours of practice. But only because, for some reason, 11,000 suddenly became available to a person focusing on that one thing. Everyone with 10,000 hours of practice would still have the same skill as they did when 10,000 hours was the maximum, it would just be that those who fully devoted themselves to that skill would all now have the skill of 11,000 hours underneath them.

The takeaway is that amassing more time on something than others is key to becoming comparatively good at it. Gladwell’s conclusion shouldn’t really have been about the number of hours spent on a thing endowing him with an expert quality, but that becoming the best at something means pushing aside other interests and focusing single-mindedly on that thing alone.

It thus raises a major question for those seeking wisdom. When it comes to developing applied wisdom, you have to decide early on what kind of capable you want to be. Do you want to be reasonably capable in many skills, or the best at one skill? I have said that for certain kinds of success, particularly financial success, it seems focusing all your efforts on one skill is best. However, it is far from obvious to me that this kind of success is actually worth the necessary tradeoff of sacrificing skill in all other areas of life. Perhaps you would actually prefer a modest life full of a wider range of interests. That is a serious question more people should probably ask themselves at a younger age.

The one hard lesson from this is that a person’s time, especially in youth, should be spent at least doing something rather than nothing. Whether you are developing one specific skill to perfection or a range of skills to competence, you can’t do either in a state of inactivity. Video games, phones, and television are easily the main scapegoats for the kind of idleness that is counter-indicated for applied wisdom. The primary advice for developing applied wisdom is to develop hobbies and interests that get you doing things. If you can get into doing things that develop broadly applicable skills like building relationships, speaking, building things, writing, and athletics, all the better. My inclination would be to advise young people especially to avoid sedentary activities whenever possible, even if that means simply being open to doing new things that come up. Simply accepting an invitation to a barbeque is superior to declining and staying at home because at least at the barbeque you will be practicing meeting and building relationships with new people, and perhaps even perfecting your grilling technique. And who knows whether some issue might arise and you get an opportunity to practice problem-solving.

Inaction and motivation

Perhaps the greatest personal disasters in life come through inaction. There are obvious examples like failing to heed natural disaster warnings or getting into legal trouble for failing to pay your taxes. But those scenarios don’t require much motivation beyond wanting to avoid the obvious pitfalls they come with. There are more subtle examples of inaction that are far more easy to succumb to.

Take anyone in a job to which they are ill-suited. If they feel reasonably comfortable in the job, they may not want to upset a survivable situation for the unknown. How many people have realized their potential was wasted in a position but were unwilling to risk losing something they could tolerate?

What about missed friendships and relationships? For many people, one of the most difficult things to motivate themselves into doing is reaching out to new people. How impactful are our friendships and relationships? Yet most people are probably missing out on many impactful relationships because of inaction when it comes to forming new relationships.

Like with all things in this essay, motivation is something that only improves with practice. First of all, we learn over time that we dislike the result of failing to motivate ourselves to do something important. We learn that satisfaction is the reward for overcoming the emotional hump of demotivation. Next, we learn methods and strategies for overcoming the momentum of inaction, the fear of failure, and the paralysis of perfectionism. We learn to see all the ways we experience demotivation and find ways that work for us to sidestep or overpower them.

But none of this can be learned until we try. There are people in the world who can’t seem to take the first step toward reordering their lives. As we ignore opportunities to motivate our selves into action, the rut of inaction becomes deeper as it gets more worn in, while the muscle needed to extract ourselves from it atrophies through inaction. Being unmotivated may not exactly be a choice, but I think failing to exercise our capacity for motivation is.

Thus, there is a wisdom to motivation. A self-orienting person must both choose his path and will his steps along it. There are all manner of challenges to his taking even the first step: uncertainty, alternatives, and fear of failure, to name a few. Each of these hurdles confront him in his own particular way and no general principals of self-motivation will ever solve his inaction because he must confront them in return in their own particular ways. There doesn’t seem to be any grant internal motive force that we can speak of in a general sense. A sense of resolve is necessary, but not sufficient. Resolve, like everything else we can speak of in terms of intellect or knowledge, is limited to the mind. It is the part for which we have no words, the crossing over of a resolve in the mind into an action of the hands, that is needed.

Only with time do we really come to internalize the lessons of inaction and action. We come to recognize the scarcity of opportunities and costs of passing them by. We come to realize the overgrown size of our fears and the unreasonable demands of our perfectionism. We come to realize that we can do things, but only if we start them. We learn that failing by doing is better than failing by not trying. In the end, we become a person capable of action because we have practiced being a person of action.

Conclusion

So, we have seen that humility opens us to wiser decisions. We see beyond ourselves and to better options only when we can admit our imperfection. And in doing so, we open ourselves to general wisdom as our experiences continually give us practice in dealing with knowledge and the lack of knowledge. If we remain humble to these experiences, we come to better understand knowledge itself. And this progression only solidifies into an actual wise ordering of our lives when we translate our more practiced use of knowledge into action.

Lastly, the step into action now brings us into new experiences. New experiences give us new opportunities to practice humility, new moments of insight when we see how something we knew deceived us or fit into a larger picture, new instances of how something we knew led to an opportunity for success, and new instances where something we thought we knew was incomplete and led to mistakes and failure. But all things we couldn’t have experienced if we hadn’t acted in the first place. Actions become moments of failure or even partial failure, those become moments of humility, and moments of humility become experience that increases our wisdom.

This, I think is the general cycle of wisdom, humility, experience, action, and back to humility. However much of this is intuitive, the unintuitive part of it is worth integrating into our lives. While the fear of acting foolishly should be taken seriously, if it becomes paralyzing, it interrupts our ability to grow in wisdom.